Some Marathon Rally History

The 1977 London to Sydney Marathon was the fourth, the longest, and the last in a series of post war inter-continental marathon car rallies that began in 1968.

Over 60 years earlier five motoring pioneers had taken up the 1907 challenge announced in the Paris newspaper, ‘Le Matin’. "What needs to be proved today is that as long as a man has a car, he can do anything and go anywhere. Is there anyone who will undertake to travel this summer from Peking to Paris by automobile?" The 1907 event was eventually won by Prince Borghese and Ettore Guizzardi driving a 7 litre Itala. From that time on motoring events would become vastly shorter affairs until the modern marathon era began.

1968

The 1968 London-Sydney Marathon was the first modern reincarnation of the marathon idea. It was sponsored by the Daily Expess and Sydney Telegraph. The challenge was 10,000 miles in ten days, for a prize of £10,000.

It was not as tough or demading as follow-up events but the 1968 London-Sydney Marathon captured the public's imagination as a true epic. At a time when the Daily Express was on just about every breakfast table in the United Kingdom the event generated a mass following making celebrities of the competing crews.

The idea had been schemed up over a roast-beef lunch in the The Savoy Grill by three Daily Express executives, Sir Max Aitken, Tommy Sopwith, and Jocelyn Stevens, looking for inspirational ways to make The Daily Express a talking point throughout the land. At the time, Britain was in a depression, the pound had been devalued, cars were not selling, unemployment was rising, and newspapers were preoccupied with doom and gloom. “A race half way round the globe for ordinary showroom cars would be a beacon of what the British motor-industry is made of” was the sort of flag-waving logic of the Express management. Millions would be cheering – they could make sure of that with trumped up promotion-stories, often on the front page, for weeks before the start, ranging from show-business diary stories and fashion shoots, to feature articles on how the RAF developed special survival-rations.

All of this proved successful – over half a million people packed the start at Crystal Palace, and several more millions lined the roads to Dover. After that, you needed the Daily Express to keep up with the changing fortunes of crews that soon became household names.

Andrew Cowan pulled off a surprise win in an ultra-reliable Hillman Hunter, from Paddy Hopkirk’s 1800 “Landcrab”…. everything was unexpected. The Ford factory team pinned their hopes on well developed Ford Cortina twin-cams with drivers such as Roger Clark... all five suffered engine problems. Hairy Australian V8s were tipped to figure, they didn’t, but Zasada’s Porsche 911 so nearly pulled it off, and Citroen were the moral winners, as their DS was leading by a country mile before it hit a Mini on the final run in to Sydney.

Among the competitors on this event was car #78, a hybrid Ford Escort GT, built and driven to an overall 45th placed finish, by Jim Gavin, the boss of Acton based tuning company Super Sport Engines. Jim Gavin would be a central character in the history of marathon car rallies in this era and would later become the lynch pin behind the organsation of the '77 London to Sydney Rally

1970

The 1970 London-Mexico World Cup Rally was the brainchild of Australian advertising guru Wylton Dickson, possibly inspired by the earlier 1968 London-Sydney Marathon.

Dickson conceived the idea of a “World Cup Rally” starting from Wembley stadium with a finish in Mexico City timed to coincide with the FIFA World Cup soccer finals. Paddy Hopkirk recalls meeting Wylton Dickson at a party in London.

“Wylton stood with a glass of wine in his hand and developed the whole idea as he was talking... it just sort of grew in his brain as we chatted – he sought my advice on who he should talk to, and I said, well, get the F.A. on side if you want to tie it in with football, and talk to Stuart Turner at Ford... in fact, a few days later, I called up Stuart Turner, and proceeded to tell him I had just met this advertising bloke who had a brainwave. After a long pause, Turner replied: ‘I know. I’ve heard all about it.’ From that moment on, Wylton Dickson was driving the idea flat out, to anyone who would listen.”

Dickson had never driven in a rally, and later admitted he had never even been to see one. His often brusk and abrasive nature with motoring-journalists, who didn’t see any “motor-sport street-cred”, was an attitude that didn’t help him win many friends, and the RAC and others saw in him someone who could skim off cars and drivers from existing championships and smaller events... but he managed to make it all happen, gaining support from the Daily Mirror and even talking the RAC into setting up a dedicated office in their building. The event attracted both works teams and celebrities including footballer Jimmy Greaves, who finished a very creditable sixth, and HRH Prince Michael of Kent who failed to finish

British rally champion John Sprinzel headed the organising team with a secretariat housed in a basement office of the Belgrave Square HQ of the RAC. His staff included route-assistant John Brown, and former BMC international navigator Tony Ambrose. Relations between the three became fractious at times as the event grew, and the enormity of the undertaking developed. A tiny band of marshals relied on small aircraft and rental cars to reach the checkpoints along the route. It all seemed rather hit and miss at times, but, in fact the event ran almost like clock-work.

One of those travelling marshals who was to play a big role in subsequent marthons was Jim Gavin, who had competed on the earlier London to Sydney in 1968.

The 1970 World Cup Rally is a site devoted to this event.

1974

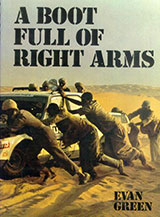

Probably one of the finest long distance rally books. Long out of print but you might find one through bookfinder.com or other sources

The 1974 UDT London-Sahara-Munich World Cup Rally was the third marathon in the series and the first-ever rally to run across the Sahara – pre-dating the first Paris Dakar by six years.

A highly ambitious route planned by Henry Liddon and Jim Gavin would set out from London's Wembley Stadium before crossing the Sahara through Algeria and Niger to reach Kano in Nigeria. From Kano the crews would turn north to cross the Sahara a second time via Tunisia to finish in Munich in time for the World Cup soccer finals.

Sponsored by the motor trade specialist finance house, United Dominions Trust, the U.D.T. World Cup Rally London-Sahara-Munich was won by a Citroen that had been prepared in a back garden by Jim Reddiex from Brisbane, Australia. His only problem was a blown rear stop-light bulb, beating several factory Peugeot 504s. In penalty terms second placed Christine Dacremont was a week behind the winner. Stirling Moss in a Mercedes nearly lost his life when he became stranded, off route, when the battery split apart – he was rescued in the nick of time by route-manager Jim Gavin, who had spent three days wringing his hands in front of Algerian officials pleading to help him mount a search party.

The event nearly fell apart at the bottom of the Sahara before Tamanrasset. The route notes said turn left when the tarmac ends, but, meanwhile, the road workers had extended the tarmac several miles, and the rally didn’t have a course-car. Even if it had, there was no way a course-car could have communicated a major change in the route. A few crews, including the winner, turned off at the correct point in the route-notes, disregarding the fact that the tarmac went straight on, found the correct track, and made the control in Tamanrasset, but many were to become hopelessly grounded – miles off route – in the wildest part of southern Sahara.

It’s a wonder the event happened at all – the stubborn tenacity of Wylton Dickson came into its own as he was stonewalled by manufacturers who made vague promises, and no commitments, and private entrants struggled to raise sponsorship. The whole event was set against another economic recession, Britain was in the middle of a three-day week, petrol was on ration, causing long queues at garage forecourts, the miners were on strike, electricity blackouts were so common Government Ministers urged the population to “clean your teeth in the dark and share a bath”.

"Car rallies across the Sahara?".... Ford who had done so well out of the London to Mexico that they named a brand new Escort model after it now shunned the whole idea – Wylton Dickson became the loneliest man in motorsport.

The UDT World Cup Rally is a web page devoted to the 74 event.